3. Translation process

Here we study variants of the machine assisted translation process, to develop a version that suits MOLTO.

The translation industry workflow

To have a point of comparison, we review the practices in the professional translation industry today. Going beyond the 90's single-user computer-assisted translation (CAT) setup with a translation editor, translation memory, and termbase, current translation management system (TMS) packages provide tools for managing complex translation industry projects involving clients, project managers, and a distributed pool of translators, reviewers, and subject experts. Many aspects of the workflow and the associated communication (notification, document transfer) can be automated in these systems. For an example of a translation industry workflow, we take the ]project-open[ Translation Workflow. Tasks typically covered by translation project and workflow management packages include

- Analyzing source text using a translation memory

- Generating quotes for the customer

- Generating purchase orders for providers and freelancers

- Executing the project

- Monitoring the project

- Generating invoices to the customer

- Generating invoices for providers and freelancers

Roles within the translation workflow

In ]project-translation[ five user roles can be defined.

- Translator: A person responsible to execute the translation and/or localization projects.

- Project Manager: A person responsible for the successful execution of projects. Project Managers frequently act as Key Account managers in small translation agencies.

- Senior Manager: Is responsible for the financial viability of the business and is the ultimate responsible for the relationships to customers

- Key Account Manager: A person responsible for the relationship to a number of customers. We assume that customer project requests are handled by a Key Account Manager and then passed on to a project Manager for execution.

- Resource Manager: A person responsible for the relationship with translation resources and providers.

GlobalSight has yet more default roles:

- Administrator

- Customer

- LocaleManager

- LocalizationParticipant

- ProjectManager

- SuperAdministrator

- SuperProjectManager

- VendorAdmin

- VendorManager

New roles can be invented at will in GlobalSight. As discussed in the MOLTO requirements document (Deliverable 9.1), The role cast in MOLTO can have at least these roles:

- Author

- Editor

- Translator

- Reviewer (domain/language expert)

- Ontologist

- Terminologist

- Grammarian

The Project Cycle

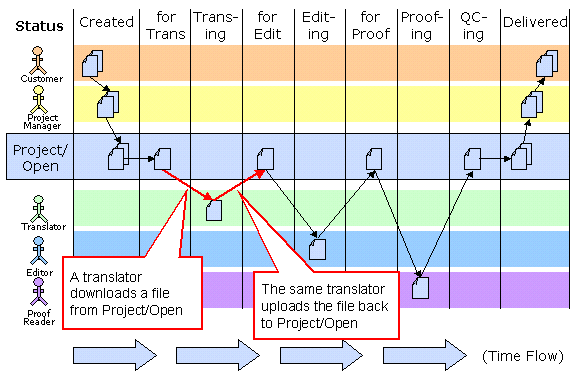

The figure below shows in a schematic way in which the workflow proceeds:

- A document from the customer is passed to the project manager for translation (This action is represented by the arrow from documents in the upper left corner from the client to the project manager).

- The Project Manager uploads the document into the ]project-open[ System

- A translators downloads the file

- The same translators uploads the translated files

Similarly for editors and proofreaders. Finally, the project manager retrieves the document and sends it to the customer. Alternatively, the project manager can allow the customer to download the files directly. In addition to tracking the status of a project at every stage, the system allows the project manager to allocate projects to the most suitable team and streamline the freelancers’ job.

GlobalSight

GlobalSight (http://www.globalsight.com/) is an open source Translation Management System (TMS) released under the Apache License 2.0. Version 8.2. was released on Sept 15, 2011. As of version 7.1 it supports the TMX and SRX 2.0 Localization Industry Standards Association standards.[2] It was developed in the Java programming language and uses MySQL database and OpenLDAP directory software. GlobalSight also supports computer-assisted translation and machine translation.

According to the documentation the software has the following features:

- Customizable workflows, created and edited using graphical workflow editor

- Support for both human translation and fully integrated machine translation (MT)

- Automation of many traditionally manual steps in the localization process, including: filtering and segmentation, TM leveraging, analysis, costing, file handoffs, email notifications, TM update, target file generation

- Translation Memory (TM) management and leveraging, including multilingual TMs, and the ability to leverage from multiple TMs

- In Contect Exact matching, as well as exact and fuzzy matching

- Terminology management and leveraging

- Centralized and simplified Translation memory and terminology management

- Full support for translation processes that utilize multiple Language Service Providers (LSPs)

- Two online translation editors

- Support for desktop Computer Aided Translation (CAT) tools such as Trados

- Cost calculation based on configurable rates for each step of the localization process

- Filters for dozens of filetypes, including Word, RTF, PowerPoint, Excel, XML, HTML, Javascript, PHP, ASP, JSP, Java Properties, Frame, InDesign, etc.

- Concordance search

- Alignment mechanism for generating Translation memory from previously translated documents

- Reporting

- Web services API for programmatic access to GlobalSight functionality and data

- Integrated with Asia Online APIs for automated translation

GlobalSight Web Services API

GlobalSight provides a web services API (http://www.globalsight.com/wiki/index.php/GlobalSight_Web_Services_API). It is used to integrate external systems to GlobalSight in order to submit content to the localization/translation work-flow, and monitor its status. The Web services API allows any client to connect and exchange data with GlobalSight, regardless of its implementation technology or operating system. The web service provides methods for

- Authentication

- Content Import

- Project management

- Activity and task management

- User management

- Locale management

- Job management

- Content export

- Documentum support

- Translation Memory management

- Term Base management

- CVS support

For convenience, we shall borrow parts of the MOLTO extended API from the GlobalSight translation management system.

The web localization workflow

The translation industry workflow is top-down controlled, built on email and file transfers. For a more collaborative bottom-up approach, we can look at web localization. Web platforms are getting localized by a collaborative translation workflow. Here, translation is typically crowdsourced to a pool of volunteers, who either translate manually online or download po files to work on with local tools. The website coordinates the effort. Different projects may have assigned managers that monitor the collaboration. It is exemplified by the Translate toolkit (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Translate_Toolkit) used to collaboratively localize open source software packages.

An instance of the Translate toolkit is Pootle http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pootle, an online translation management tool with translation interface. It is written in the Python programming language using the Django framework and is free software originally developed and released by Translate.org.za in 2004. It was further developed as part of the WordForge project and the African Network for Localisation and is now maintained by Translate.org.za.

Pootle is intended for use by free software translators but is usable in other situations. Its main focus is on localization of applications' graphical user interfaces as opposed to document translation. Pootle makes use of the Translate Toolkit for manipulating translation files. The Translate Toolkit also offers offline features that can be used to manage the translation of Mozilla Firefox and OpenOffice.org in Pootle. Some of Pootle's features include terminology extraction, translation memory, glossary management and matching, goal creation and user management.

It can play various roles in the translation process. The simplest displays statistics for the body of translations hosted by the server. Its suggestion mode allows users to make translation suggestions and corrections for later review, thus it can act as a translation specific bug reporting system. It allows online translation with various translators and lastly it can operate as a management system where translators translate using an offline tool and use Pootle to manage the workflow of the translation.

The Translate Toolkit API is documented at http://translate.sourceforge.net/doc/api/. It is open source subject to the GPL licence. The Google Translator Toolkit

Google provides a free service for translating webpages by post-editing Google MT results. The toolkit allows users to

- Upload and translate documents

- Use documents from your desktop or the web.

- Download and publish translations

- Publish translations to Wikipedia™ or Knol.

- Chat and share translations online

- Collaborate online with other translators.

- Use advanced tools like translation memories and multilingual glossaries.

The Google Translator Toolkit Data API allows client applications to access and update translation-related data programmatically. This includes translation document, translation memory, and glossary data stored with Google Translator Toolkit. The Google Translator Toolkit API is now a restricted API (http://code.google.com/apis/gtt/).

The MOLTO translation workflow

We now consider the MOLTO translation scenario. The MOLTO translation demo editor (see figure further below) supports a one-person workflow where the same person is the author(ised editor) of the source and the translator. Technically we can extend this to a more collaborative scenario where more actors are involved as in the professional workflow above, by adding the usual project support tools to the toolkit. A more difficult part is to adjust the workflow so that the adaptivity goal above is satisfied. In the professional workflow, corrected translations accumulate in the translation memory, which helps translators avoid the same errors next time. In the MOLTO workflow, GF has an active role in generating translations, so it is GF that should learn from the corrections. Concretely, when a translator or reviser changes a wording, the correction should not go unnoticed, but should find its way to back to the GF grammar, preferably through a round of community checks.

We next try a description of one round of the ideal MOLTO translation scenario.

Although it is possible that an author is ready to create and translate in one go (especially in a hurry), it is more normal to have some document(s) to start from. The document/s might be created in a GF constrained language editor in the first place. In that case, the only remaining step is translation. If translation coverage and quality has been checked, nothing more is neeeded. But frequently, some changes are needed to a previously translated document, or a new one is to be created from existing pieces and some new material. Imaginably, some of the parts come from different domains, and need to be processed with different grammars. Some such complications might be handled with document composition techniques in the manner of Docbook or DITA toolchains.

The strength of GF is that it ought to handle grammatical variation of existing sources well, so as to avoid manual patching of previous translations. Assume there is a previously GF translated document, and we want to produce a variant. Then it ought to be enough to load the document, make desired changes to it under the control of the GF grammar, and let GF generate the modified translations.

Is it necessary to show the translations to the user? Not unless the translator knows the target language(s). We should distinguish two profiles: blind translation, where the author does not know or is not responsible for the target languages herself, but relies on outside revision, and plain translation, in which there is one or two target language known to the author/translator to translate to, who wants to check the translations as she goes.

In the blind profile, the author has to rely on revisers, and the revision cycle is slower. The revisers can either notify the author that the source does not translate correctly in their language(s), or they may notify the grammar/lexicon developer(s) directly, or both. If there is a hurry, the reviser/s should provide a correct translation directly for the author/publisher to use as canned text. In addition, they should notify the grammar developer/s of the revisions needed to GF. The notification/s could happen through messages, or conveyed through a shared translation memory, or both. In this slower cycle, it may not be realistic to expect the author to change the source text and repeat the revision process many times over for the same source and possibly a multiplicity of languages to get everything translate right before publication.

In the plain profile, a faster cycle of revision is called for. The author/translator can try a few variations of the input. If no variant seems to work, then she probably wants to use her own translation, but also to make sure that GF learns of and from the failure. The failure can be a personal preference, or a general fix that the community should profit from. If it is a personal preference, the user may want to save the corrected translation in her translation memory and/or glossary, but also she may want to tweak her GF grammar to handle this and similar cases to her liking next time. If it is just a lexical gap or missing fixed idiom, then there should be in GF translation API a service to modify the grammar without knowing GF. The modifications could happen at different levels of commitment. The most direct one would be to provide a modular PGF format which would allow advising the compiled user grammar on the fly. Such a runtime fix would make sure that the same error will not happen during the same translation session or subsequent ones at least until the domain grammar is recompiled.

The next level of commitment to a change would be to generate new GF source, possibly from example translations provided by the author/translator, compile them, and add the changed or extra modules to the user's GF grammar. The cycle involved here might be too slow to do during translation, but it could happen between translation sessions. If fully automatic grammar revision is too error prone, the author/translator could just go on with canned translations in this session, and commit change requests to the grammar developer community. In this case, the changes would be carried out in good time, with regression tests and multilingual revision cycles, especially if the changes affect the domain semantics (abstract grammar) and thereby all translation directions.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| workflow.png | 10.68 KB |