1.1 The MOLTO Translation Workflow

olga.caprotti

Multilingual Online Translation

The MOLTO TT (translation tools) editor supports a one-person workflow where the same person is the author(ised editor) of the source and the translator. The adoption of the GlobalSight TMS to MOLTO allows embedding it in a more collaborative scenario where more actors are involved as in the professional workflow described in the API document, by adding traditional CAT and translation project support tools to the toolkit. A more difficult part is to adjust the workflow so that the adaptivity goal is satisfied. In the professional workflow, corrected translations accumulate in the translation memory, which helps translators avoid the same errors next time. In the MOLTO workflow, GF has an active role in generating translations, so it is GF that should learn from the corrections. Concretely, when a translator or reviser changes a wording, the correction should not go unnoticed, but should find its way to back to GF, preferably through a round of community checks. More generally improvements should be shared by the community, so that the whole community acts adaptively.

We next try a description of one round of the ideal MOLTO translation scenario.

Although it is possible that an author is ready to create and translate in one go (especially in a hurry), it is more normal to have some document(s) to start from. The document/s might be created in a GF constrained language editor in the first place. In that case, the only remaining step is translation. If translation coverage and quality has been checked, nothing more is neeeded. But frequently, some changes are needed to a previously translated document, or a new one is to be created from existing pieces and some new material. Imaginably, some of the parts come from different domains, and need to be processed with different grammars. Some such complications might be handled with document composition techniques in the manner of Docboook or DITA toolchains.

The strength of GF is that it ought to handle grammatical variation of existing sources well, so as to avoid manual patching of previous translations. Assume there is a previously GF translated document, and we want to produce a variant. Then it ought to be enough to load the document, make desired changes to it under the control of the GF grammar, and let GF generate the modified translations.

Is it necessary to show the translations to the user? Not unless the translator knows the target language(s). We should distinguish two profiles: blind translation, where the author does not know or is not responsible for the target languages herself, but relies on outside revision, and plain translation, in which there is one or two target language known to the author/translator to translate to, who wants to check the translations as she goes.

In the blind profile, the author has to rely on revisers, and the revision cycle is slower. The revisers can either notify the author that the source does not translate correctly in their language(s), or they may notify the grammar/lexicon developer(s) directly, or both. If there is a hurry, the reviser/s should provide a correct translation directly for the author/publisher to use as canned text. In addition, they should notify the grammar developer/s of the revisions needed to GF. The notification/s could happen through messages, or conveyed through a shared translation memory, or both. In this slower cycle, it may not be realistic to expect the author to change the source text and repeat the revision process many times over for the same source and possibly a multiplicity of languages to get everything translate right before publication.

In the plain profile, a faster cycle of revision is called for. The author/translator can try a few variations of the input. If no variant seems to work, then she probably wants to use her own translation, but also to make sure that GF learns of and from the failure. The failure can be a personal preference, or a general fix that the community should profit from. If it is a personal preference, the user may want to save the corrected translation in her translation memory and/or glossary, but also she may want to tweak her GF grammar to handle this and similar cases to her liking next time. If it is just a lexical gap or missing fixed idiom, then there should be in GF translation API a service to modify the grammar without knowing GF. The modifications could happen at different levels of commitment. The most direct one would be to provide a modular PGF format which would allow advising the compiled user grammar on the fly. Such a runtime fix would make sure that the same error will not happen during the same translation session or subsequent ones at least until the domain grammar is recompiled.

The next level of commitment to a change would be to generate new GF source, possibly from example translations provided by the author/translator, compile them, and add the changed or extra modules to the user's GF grammar. The cycle involved here might be too slow to do during translation, but it could happen between translation sessions. If fully automatic grammar revision is too error prone, the author/translator could just go on with canned translations in this session, and commit change requests to the grammar developer community. In this case, the changes would be carried out in good time, with regression tests and multilingual revision cycles, especially if the changes affect the domain semantics (abstract grammar) and thereby all translation directions.

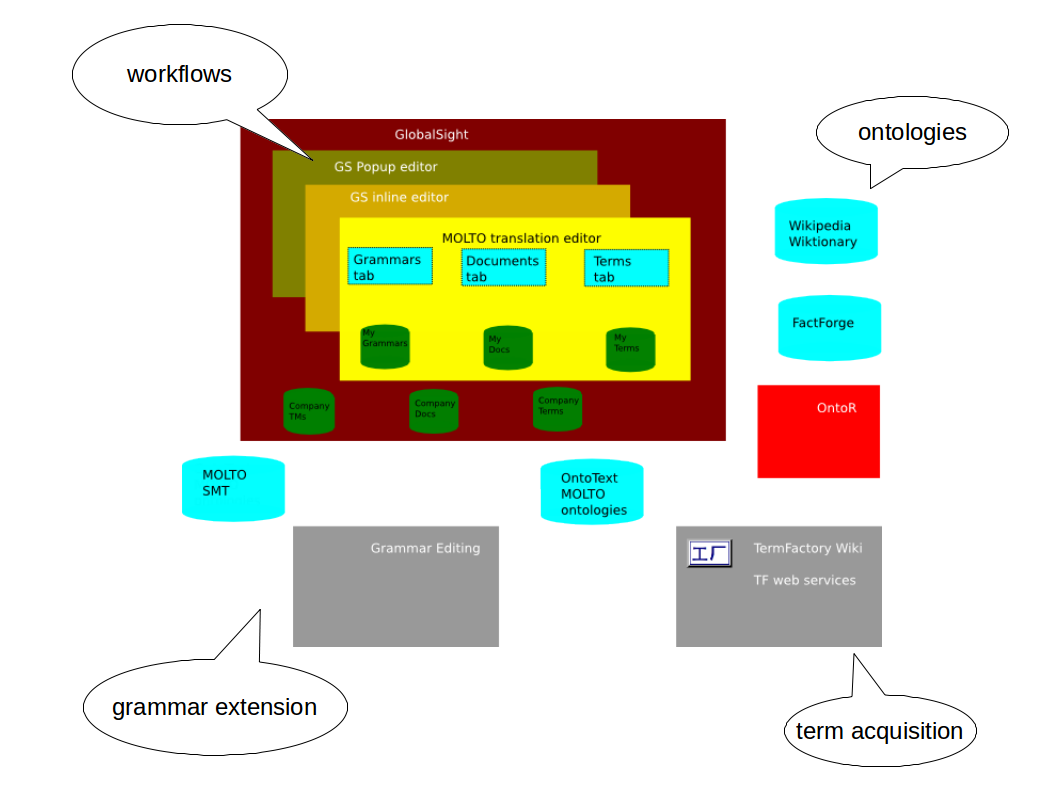

Here is a figure of the overall design.